The Kendeda Building is Among the Greenest in the World. It Achieved Living Building Challenge 3.1 Certification in 2021—the First in Georgia and the 28th in the World.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

What is the Living Building Challenge?

The Living Building Challenge (LBC) is a philosophy, advocacy tool, and certification program from the International Living Future Institute (Living Future) defining today’s most advanced measure of sustainability in the built environment.

The LBC is a rigorous, performance-based standard. Fully certified projects must meet all of the objectives contained in seven performance areas or “Petals” that are divided into 20 requirements called “Imperatives.” The project must prove that it is net-positive water and energy over a minimum of 12 months of continuous occupancy and operations.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Photo courtesy of Gregg Willett

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Petals and Imperatives: a Flower Metaphor

Like flowers that thrive within their ecosystem, The Kendeda Building sustains itself while inspiring future advocates for better buildings. Its "seeds"—students, visitors, and project teams—carry its lessons forward. Not every seed germinates, but by proving that Living Buildings are possible in the Southeast, The Kendeda Building helps shift the paradigm from “less bad” to buildings that give back more than they take.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Photo courtesy of Gregg Willett

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Petal: Place

Imperative 02: Urban Agriculture

Rooftop Garden

Like most spaces in The Kendeda Building, the rooftop garden serves many purposes and helps contribute to the building’s performance. The approximately 5,000 square foot rooftop garden consists of a honeybee apiary, pollinator garden, blueberry orchard, and a laboratory. These elements help satisfy the Urban Agriculture Imperative requirement while simultaneously offering valuable curriculum and research opportunities.

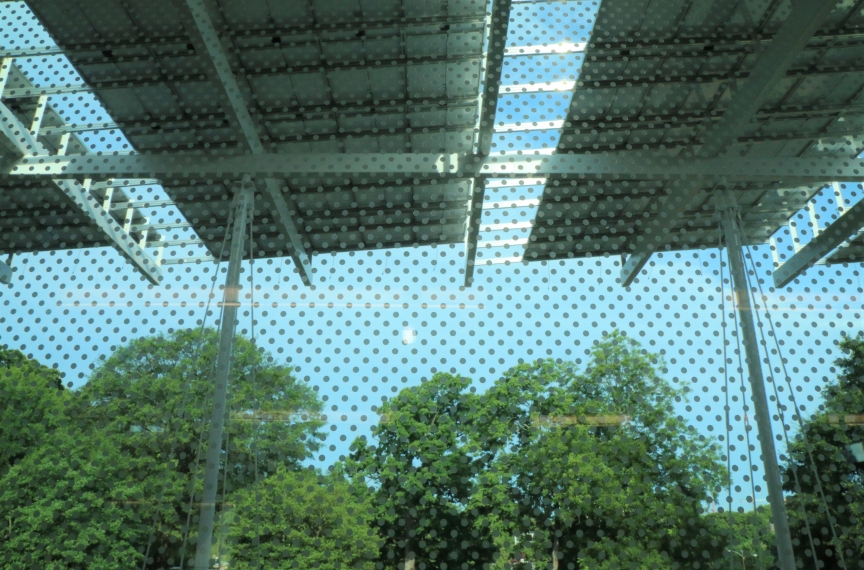

As with most rooftop gardens, The Kendeda Building contains catchments to help manage rainwater runoff. It also helps mitigate the urban heat island effect by reducing the amount of heat radiated back into the surrounding area. The PV array overhangs onto the rooftop garden providing occupants with shade thereby extending its use into more months of the year.

The Kendeda Building provides a model for sustainable and productive infrastructure that supports pollinators and pollinator habitat conservation awareness. The Georgia Tech Urban Honey Bee Project is an interdisciplinary undergraduate research and education program focused on the impact of urban habitats on honey bees. This unique program has located their hives on The Kendeda Building rooftop garden.

Petal: Beauty

Imperative 20: Inspiration + Education

A Flexible Auditorium

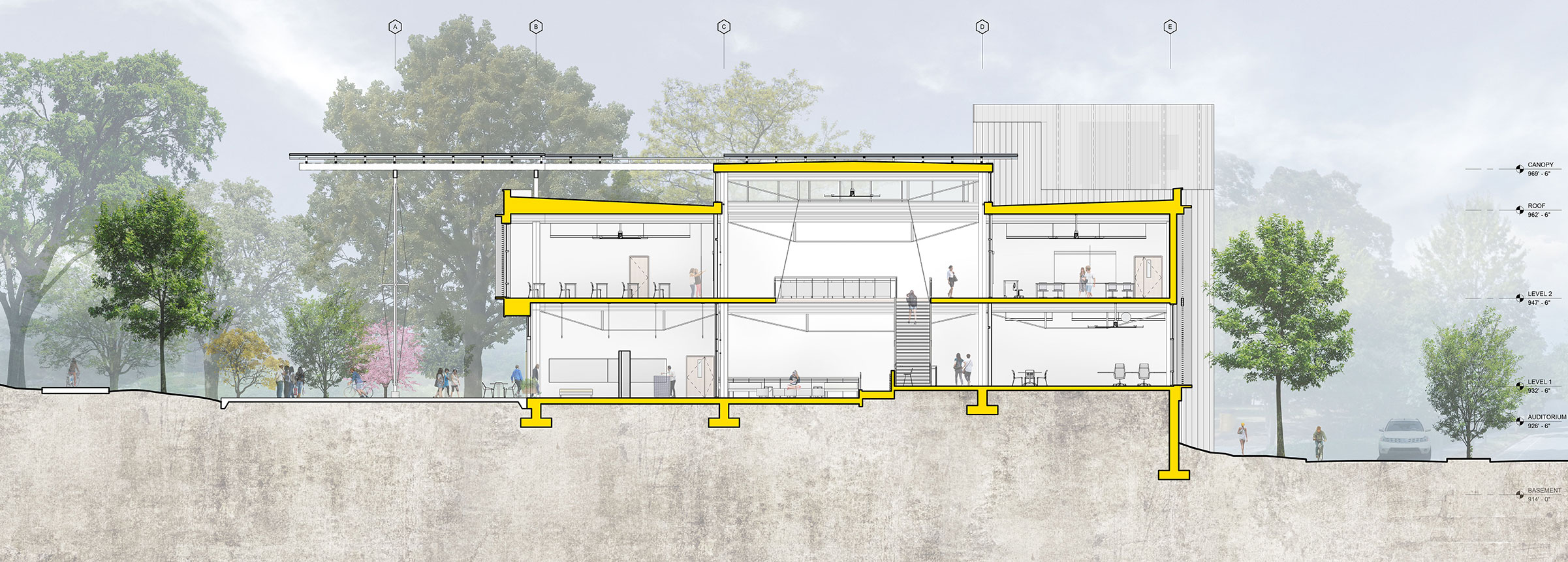

The Kendeda Building is a multidisciplinary, non-departmental academic space. Rather than serving a single subject like architecture or civil engineering, it was intentionally designed to welcome a broad range of students and introduce them, through the built environment, to regenerative design in action.

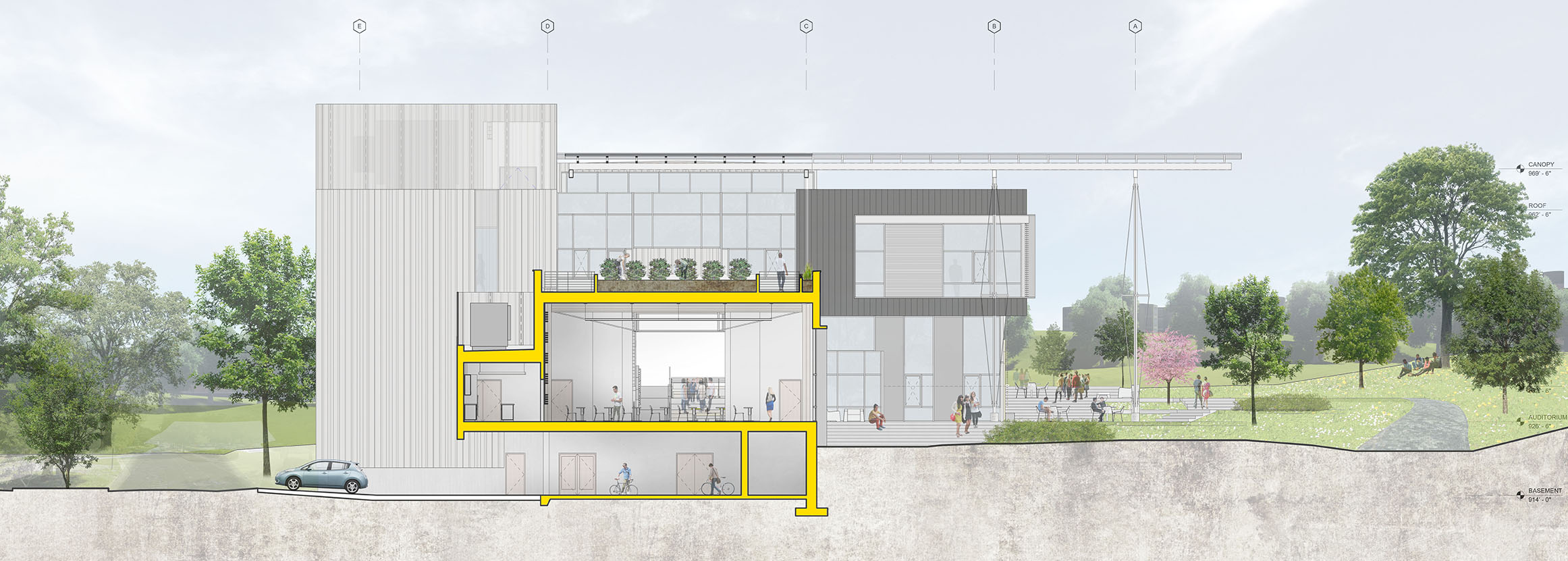

At the core of the building is a flexible auditorium that seats 176 in a classroom layout. Large enough to host high-enrollment courses across disciplines, it also supports lectures, symposia, workshops, and major public events, for example an Atlanta mayoral debate, a town hall with the U.S. Secretary of Energy, and a tri-state governors' summit featuring Georgia, Tennessee, and Virginia.

A large “garage door” at the auditorium’s entrance opens into the atrium, allowing events to spill into the shared space. While many gatherings center on sustainability, others embody the Equity Petal’s ethos by welcoming a diversity of perspectives and purposes.

Petal: Equity

Imperative: None; the team implemented its own Equity ethos

Workforce Development

While the project meets all the required Imperatives for the Equity Petal, the project team thought more broadly about how The Kendeda Building could further equity in the built environment. The team decided to partner with Georgia Works!, a non-profit program that trains and employs economically disadvantaged residents of Atlanta. The exposed wood floor/ceiling assembly, which is a key design feature of the building, was constructed largely by six Georgia Works! personnel. This provided them with valuable on-the-job training that helped them move their lives forward.

Petal: Equity

Imperative 16: Universal Access to Nature & Place

Access For All Occupants

The Living Building Challenge envisions communities that allow equitable access and treatment to all people regardless of physical abilities, age, or socioeconomic status. The Kendeda Building is designed for universal access to and throughout the site and the building for all occupants. For example, the ramp is in the center of the building, directly adjacent to the stairs thereby ensuring that all people have similar experiences throughout the project.

Georgia Tech extended this equitable access ethos to the types of classes taught and events held in the building. The design team envisioned a building that is welcoming to the broadest cross section of the community. The goal is to have as many people circulate through the building as possible so that they can be inspired by its regenerative design.

Petal: Materials

Imperative 14: Net Positive Waste

Preserving Georgia Tech's Heritage

Construction and demolition (C&D) debris consists of materials used in buildings and infrastructure projects (e.g., roads and bridges). According to the EPA, 569 million tons C&D debris were generated in the United States in 2017 (the most current year for which data is available). This is more than twice the amount of waste generated from municipal sources (e.g., trash generated by building occupants).

C&D debris includes materials that could be reused such as steel, wood products, brick and clay tile, and concrete. To divert otherwise reusable C&D material from the landfill, construction of The Kendeda Building had to be net positive waste, meaning more items had to be salvaged than sent to the landfill.

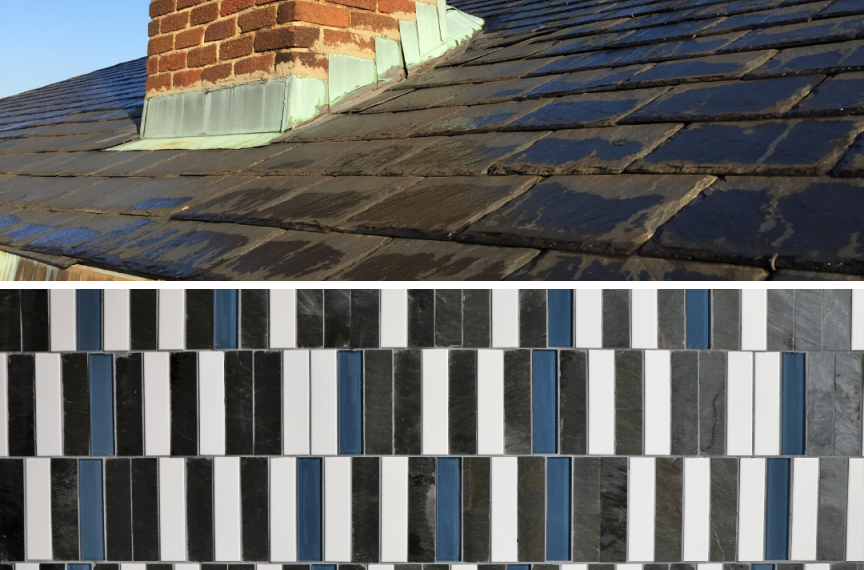

The project team took this Imperative as an opportunity to salvage materials from iconic Georgia Tech buildings and incorporate them into The Kendeda Building. Slate roof tiles from the former Georgia Tech Alumni House became bathroom tiles in The Kendeda Building. Wood from the 2017 renovations of Tech Tower, which was erected in 1888, became stair treads in The Kendeda Building (see image below provided by the Lifecycle Building Challenge). By using salvaged wood from Tech Tower to constructed the common area staircase, the project saved $60,000 as compared to purchasing new materials.

Petal: Water

Imperative 05: Net Positive Water

Constructed Wetland

Constructed wetlands are treatment systems that use natural processes involving wetland vegetation, soils, and their associated microbial assemblages to improve water quality. The Kendeda Building’s greywater (used water that does not contain organic matter) is collected from shower drains, sink drains, and water fountains to a primary tank. The greywater is pumped up to a constructed wetland at the main entrance, gravity fed to other filtration and disinfection tanks, and ultimately allowed to infiltrate back into the soil via leach fields at the north end of the site for groundwater recharge. The visible portion of the wetland is at the front door for education and aesthetic purposes.

Petal: Water

Imperative 05: Net Positive Water

Underground Cistern

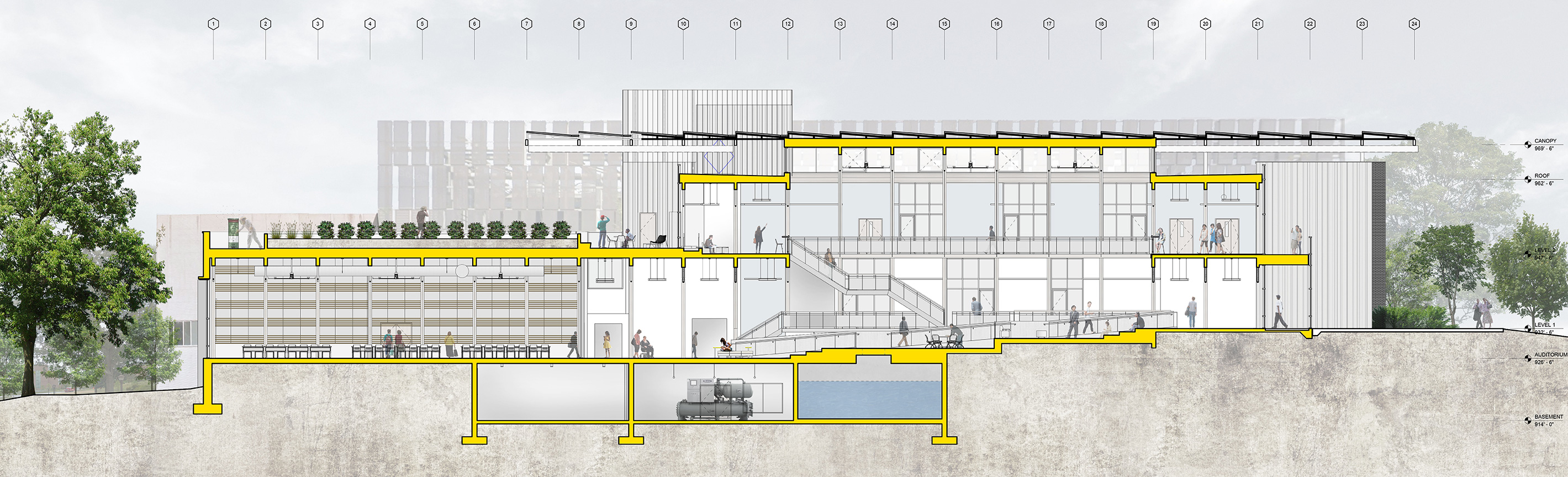

Living Buildings must minimize stormwater runoff. The Kendeda Building’s landscape mimics the Piedmont Forest’s hydrology through seepage areas, rain gardens, and permeable pavers, allowing most rainwater to absorb into the ground.

Rainwater is also collected from the solar panels, roof deck, and green roof, then filtered into a 50,000-gallon basement cistern. This system captures about 40% of annual rooftop runoff. When the cistern is full, excess water is directed to on-site stormwater systems.

Petal: Water

Imperative 05: Net Positive Water

Water Resiliency

Living Buildings are only allowed to have minimal stormwater runoff. At The Kendeda Building, most rainwater is either captured or naturally filtered into the ground. The site was designed to mimic the natural hydrology of the Piedmont Forest, using seepage areas, rain gardens, and permeable pavers to absorb excess rainwater.

Rainwater is harvested from the solar panels, roof deck, and green roof. It is filtered and routed to a 50,000 gallon cistern in the building’s basement for holding. The cistern system captures approximately 41 percent of the annual rooftop runoff. Once full, excess rainfall is released from the cistern and directed to onsite stormwater systems.

Petal: Place

Imperative 01: Limits to Growth

Site Restoration

The Kendeda Building is located on a previously developed site (formerly a parking lot) on the northwest corner of Ferst Drive and State Street on Georgia Tech’s campus. The overall design intent was to restore the site as it existed prior to human development. This goal was accomplished by mimicking the hydrological flow of the area and reintroducing vegetation and biology native to the region, referencing the Piedmont Forest ecosystem. The project site moderately slopes down from south to north, with the building and adjacent porch plaza designed to follow this natural topography by terracing, or stepping down, at appropriate elevations.

Adjacent to The Kendeda Building is another phase of Georgia Tech's EcoCommons. This new passive recreation and high performance landscape also replaced surface parking. While this EcoCommons phase is separate from The Kendeda Building, it is another example of Georgia Tech's commitment to furthering sustainability across the entire campus. The two projects were designed to be interconnected and create one cohesive whole.

Petal: Beauty

Imperative 20: Inspiration + Education

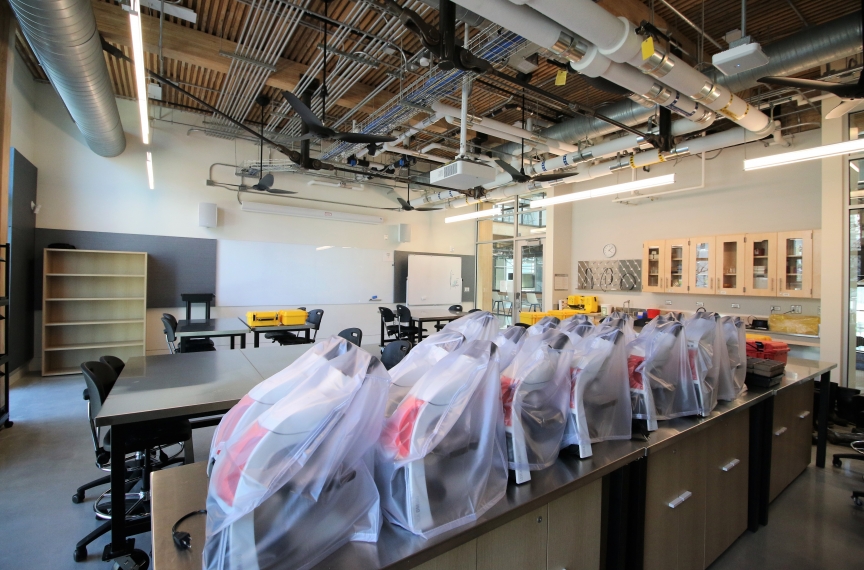

Class Labs Adjust To LBC Requirements

Much like the classrooms, the four class labs are designed to foster active learning by using The Kendeda Building as a teaching tool. This conversation began prior to the building's completion. The class labs that were slated to move into the building had never been required to consider energy and water consumption. To assist with the building becoming net positive energy and water, instructors who moved their class labs into the building changed how they teach their courses to conserve energy and water. These lessons can be applied across campus and beyond to help other class labs reduce their environmental impact.

Petal: Health & Happiness

Imperative 08: Healthy Interior Environment

Fresh Air

The Kendeda Building couples a dedicated outdoor air system (DOAS) with indoor carbon dioxide sensors located throughout the building (CO2 is a good measure of occupancy because we exhale CO2). This allows for a demand control ventilation strategy. In other words, the building automatically adjusts the amount of outside air brought into the building in response to the number of people in a given space. This approach results in improved air quality and reduced energy consumption.

Petal: Water

Imperative 05: Net Positive Water

Condensate Harvesting

Condensate from the Dedicated Outdoor Air System (DOAS) is captured and directed into the building’s rainwater management system. Instead of being wasted, this water is returned to the soil on site, helping to recharge the local groundwater and support the building’s overall water stewardship strategy.

Petal: Materials

Imperative 13: Living Economy Sourcing

Locally-Sourced Materials

The intent of the Living Economy Sourcing Imperative is to support investment in local economies that stimulates local economic growth, strengthens community ties and development, and minimizes environmental impacts associated with transportation of products and people. At least fifty percent of all the content was sourced within 621 miles (1,000 km) of the building. The project’s carpet, steel, nail laminated timber, and rigid insulation are all manufactured or fabricated in Georgia. Sustainably harvested wood was sourced from Alabama and 100% recycled content brick were made in Salsbury, North Carolina. To learn more about the brick, click here:

https://livingbuilding.kendedafund.org/2019/05/20/waste-materials-fire-green-leafs-recipe-for-100-percent-recycled-brick/

Petal: Materials

Imperative 14: Net Positive Waste

Materials Management

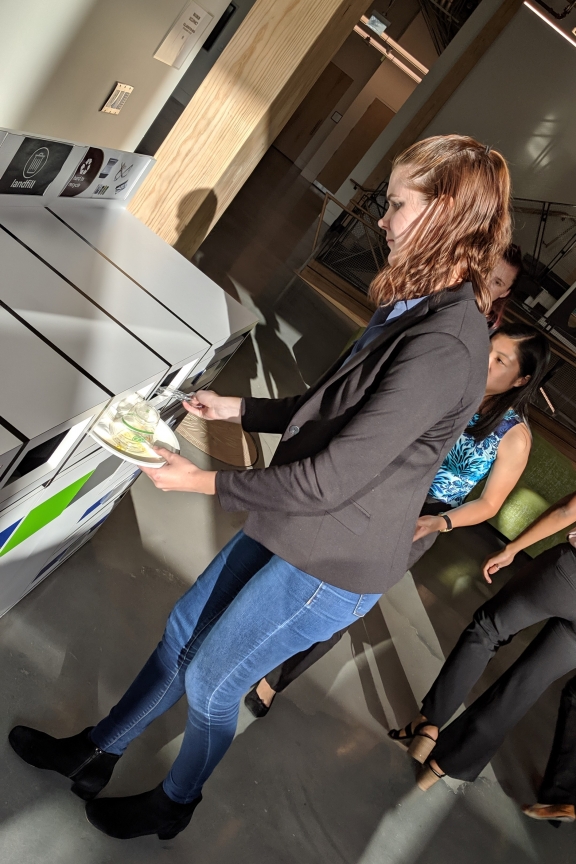

While the Living Building Challenge requirement to be net positive waste only applies to the construction process, this Imperative does require that The Kendeda Building provide dedicated infrastructure for the collection of recyclables and compostable food scraps. Georgia Teach already had a robust materials management plan for campus and The Kendeda Building is providing us with a platform to take materials management to the next level.

Reduction of waste starts prior to people entering any building. Therefore, the building's Guidelines webpage provides guidance on how to reduce waste. Catered events cannot use styrofoam or single use plastics and are requested to use reusable dishware, cups, utensils, trays, platters, and other serving ware whenever possible. Any disposable packaging and serving ware (e.g., trays, plates, platters, utensils, and cups) must be BPI-Certified compostable products.

There are three materials management stations indoors and two outdoors on the porch. The indoor materials management stations were designed by Georgia Tech students. All of the stations have bins for landfill, plastic, paper, cans, and compost. Two have drawers for hard-to-recycle products such as plastic film, batteries, and glass. In addition, there is one coffee recycling station that accepts lids, liquids, and single-use coffee cups.

CompostNow, a nonprofit compost collection service, collects the building's compostable materials. The hard-to-recycle materials are periodically transported to the Center for Hard to Recycle Materials, a local nonprofit. These two nonprofits provide measurement of material diverted. Georgia Tech measures the other categories to understand total waste diversion. Georgia Tech also conducts periodic audits to determine the level of contamination with the goal of continuously improving the materials diversion process.

Petal: Energy

Imperative: Net Positive Energy

Radiant Heating and Cooling

The Kendeda Building uses water-based radiant systems throughout most of its spaces. Tubes embedded in concrete floors circulate warm or cool water, directly heating or cooling occupants, much like the sun warms your skin, rather than conditioning the air.

Radiant systems are more efficient than traditional HVAC. Water delivers energy more effectively than air, and concrete's thermal mass helps retain temperature longer. A 1-inch pipe can move as much energy as a 12x12-inch air duct.

The system draws chilled water from Georgia Tech’s central loop for cooling. For heating, the building’s heat pumps generate hot water while producing chilled water as a byproduct, which is returned to the loop thereby reducing the load on the campus plant, similar to how excess solar power supports campus energy needs. The building’s proportional use of campus water and electricity is included in its annual net positive energy calculations.

Petal: Energy

Imperative 06: Net Positive Energy

Clerestory Windows

Operable clerestory windows at the atrium roof provide abundant daylight and natural ventilation. This simple passive design reduces reliance on artificial lighting and air conditioning, supporting the building’s net positive energy performance.

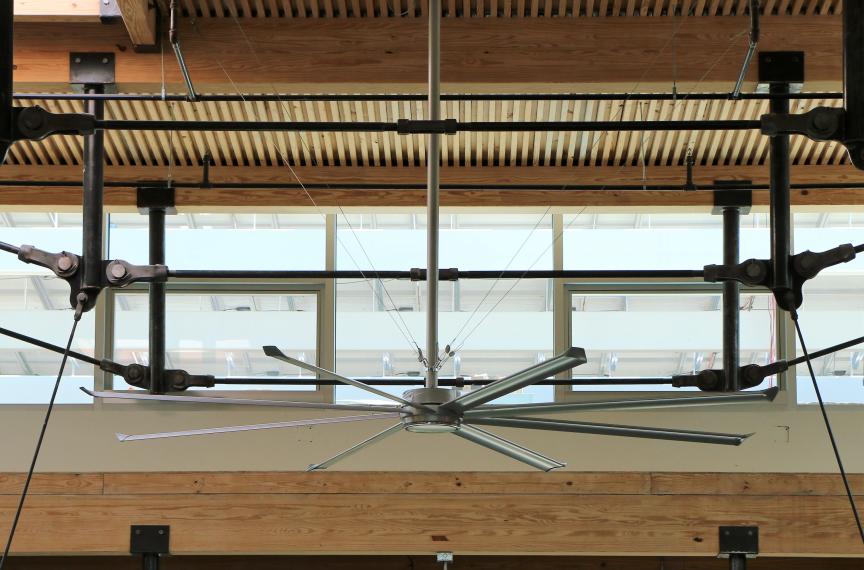

Ceiling Fans

The building has 63 ceiling fans for comfort and circulation, including four high-volume, low-velocity fans in the atrium and auditorium. Smaller fans in other areas feature motion sensors for automatic shut-off, improving energy efficiency.

Petal: Beauty

Imperative: Inspiration + Education

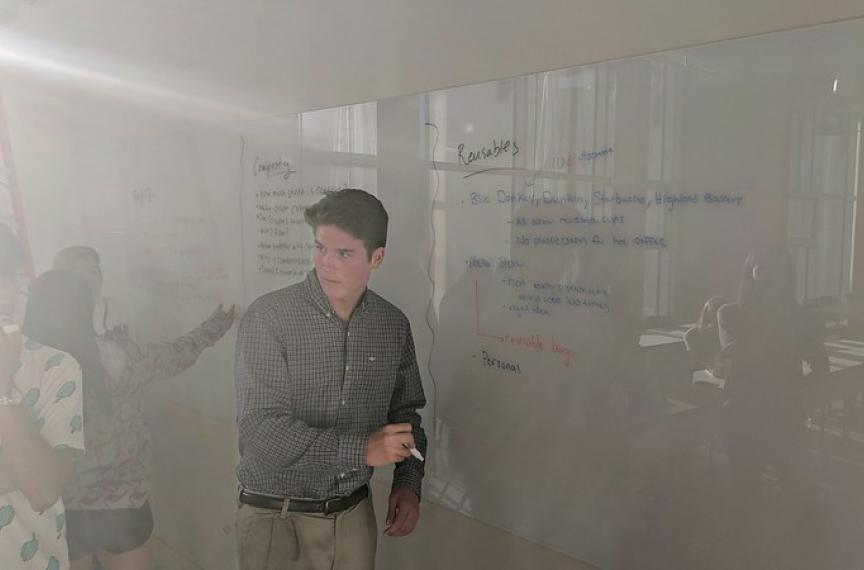

Transforming Future Generations Of Thinkers

The Kendeda Building is a multi-disciplinary, non-departmental education building designed to function as a true living, learning laboratory. The building welcomes the broadest cross section of students so that they can be inspired by its regenerative design.

The Kendeda Building helps educate and transform future generations of thinkers and doers to not only create a more sustainable environment, but one that actually gives back and improves the world. The Kendeda Building features two 64-person classrooms to provide learning opportunities across a variety of subject areas. The classrooms are on the second floor and can be accessed via the atrium.

Petal: Materials

Imperative 14: Net Positive Waste

Fostering a Salvage Economy

Construction and demolition (C&D) debris consists of materials used in buildings and infrastructure projects (e.g., roads and bridges). According to the EPA, 569 million tons C&D debris were generated in the United States in 2017 (the most current year for which data is available). This is more than twice the amount of waste generated from municipal sources (e.g., trash generated by building occupants).

C&D debris includes materials that could be reused such as steel, wood products, brick and clay tile, and concrete. To divert otherwise reusable C&D material from the landfill, construction of The Kendeda Building had to be net positive waste, meaning more items had to be salvaged than sent to the landfill.

The project reused materials from other buildings and sources on campus. For example, storm-fallen black oak, white oak, and water oak were collected, milled, and dried for “live edge” counters, tables, and benches.

The project team also partnered with the Lifecycle Building Center, an Atlanta-based nonprofit that captures building materials from the waste stream and directs them back into the community through reuse. The Lifecycle Building Center collected C&D debris from the community for use in the building. For example, 25,000 linear feet of 2x4 wood was salvaged from local film sets and incorporated into the nail laminated timber floor/ceiling assembly.

The reuse of C&D debris is an untapped economic development opportunity. Rather than sending these beneficial materials to the landfill, we can use local labor to "virtually mine" the landfills for these raw materials and divert them to construction projects. We could jumpstart such a "salvage economy" if every new building / renovation followed the Living Building Challenge's lead and incorporated at least one salvaged material per 500 square meters of gross building area.

There is a secondary benefit to diverting this material from landfills: reduction in global carbon pollution. First, reuse of material reduces the amount of energy and water required to create new material. This reduction in energy and water use also reduces the amount of greenhouse gases emitted. Second, decomposing wood in landfills releases methane, which is a potent greenhouse gas. Diverting wood from the landfill eliminates this negative impact.

Petal: Materials

Imperative 10: Red List

Healthier Materials

The Red List imperative aims to eliminate the use of 22 worst-in-class materials or chemicals (almost 800 in total) with the greatest impact to human and ecosystem health. To avoid the use of Red List materials, the design-build team thoroughly vetted proposed materials by selecting and specifying products that are documented as being free of Red List materials or chemicals. One way of vetting the materials and products was to search for products that have Cradle to Cradle Certification, Healthy Product Declaration, or Declare Label, which is a “nutrition label” for and online database of compliant building materials that was developed by the International Living Future Institute.

In addition, the team advocated for change and transparency among industry material suppliers. This advocacy by The Kendeda Building project team, as well as the project teams of existing certified Living Buildings, has shifted the market. For example, The Kendeda Building's fluid-applied air-and-water barrier is made by a company that changed its formulation to be free of Red List materials in order to be selected by the Bullitt Center, which was seeking Living Building Challenge certification. To learn more about the air-and-water barrier, click here https://livingbuilding.kendedafund.org/2019/03/29/prosoco-air-barrier-closely-tied-to-living-buildings.

In the adjacent video by Southface Institute, Eckardt Group discusses how they deployed an alternative strategy with flexible conduit that was Red List-compliant and suitable for The Kendeda Building.

Petal: Water

Imperative 05: Pet Positive Water

Rainfall Management

Our civilization's typical built environment is designed to treat natural occurrences as nuisances. For example, impervious surfaces turn rainfall, which can be beneficial, into stormwater that burdens infrastructure and often negatively impacts downstream communities.

In contrast, The Kendeda Building site treats rainfall as an asset. The outdoor areas have systems designed specifically to assist in the management of rainwater. Following the natural moderate slope from south to north, the porch terraces, or steps down, at appropriate elevations. This geometry accommodates cascading porch areas that support substantial water storage underneath the permeable pavers. Unlike a traditional stormwater management approach that concentrates water storage in a single area, this method of managing rainwater relies on dispersed locations along the sloped site in order to leverage gravity to assist in controlling the flow of water.

Petal: Water

Imperative 05: Net Positive Water

Harvesting Rainwater

Living Buildings must minimize stormwater runoff. The Kendeda Building’s landscape mimics the Piedmont Forest’s hydrology through seepage areas, rain gardens, and permeable pavers, allowing most rainwater to absorb into the ground.

Rainwater is also collected from the solar panels, roof deck, and green roof, then filtered into a 50,000-gallon basement cistern. This system captures about 40% of annual rooftop runoff. When the cistern is full, excess water is directed to on-site stormwater systems.

The solar canopy is also a key design feature that gets The Kendeda Building to net positive energy.

Petal: Health + Happiness

Imperative 09: Biophilic Environment

Connection to Nature

The Health + Happiness Petal focuses on the most important environmental conditions that must be present to create robust, healthy spaces, rather than to address all of the potential ways that an interior environment could be compromised. For example, this Imperative requires occupant access to fresh air and daylight. Therefore, The Kendeda Building has been designed to include elements that provide occupants with visual and physical connections to nature.

The building's porch will have a direct connection to the next phase of Georgia Tech's Eco-Commons, a greenspace complement to - and compliment of - the ideals of the building.

Petal: Energy

Imperative 06: Net Positive Energy

Energy Recovery System

The Kendeda Building couples a dedicated outdoor air system (DOAS) with indoor carbon dioxide sensors that determine the amount of outside air that needs to be brought into the building. The system only brings in the amount of outside air that is required by occupants (CO2 being a good measure of occupancy because we exhale CO2). Indoor air is then exhausted in order to maintain a slightly positive pressure in the building.

In the summer, cooler dehumidified indoor air leaves the building and hotter humid air enters. An enthalpy wheel, also known as a thermal wheel, in the DOAS transfers energy and humidity from the incoming hot, humid air stream to the outgoing cooler, drier air stream. This process cools and dehumidifies the outdoor hot, humid air entering the building and thereby reduces the load on the building’s other mechanical systems.

In the winter, the same concept works in reverse. The cold air entering the building is heated by warmer air being exhausted by the building.

Petal: Energy

Imperative 06: Net Positive Energy

75% Less Energy

The Energy Petal requires net positive energy, which means at least 105% of the project’s energy needs must be supplied by on-site renewable energy on a net annual basis, without the use of on-site combustion. To reduce the size of the solar array that would be needed to reach this net positive energy goal, The Kendeda Building designers focused on passive design techniques that leverage the natural climate, solar, and energy characteristics of a building and its surroundings to lower energy demands.

For The Kendeda Building, special attention was given to designing an efficient building envelope. The performance of the building envelope is critical both to the energy efficiency of the building and to the comfort level of the occupants. This includes continuous insulation at walls and under slabs and triple pane window glazing. The triple pane window's outer surface and the middle pane’s room-side surface are treated with a low-emissivity metallic coating. This reduces solar heat gain during hot weather, while the room-side coating helps with insulation during cold weather. As a result, the building has a reduced electricity load during the winter and summer seasons.

Through energy efficiency alone, The Kendeda Building consumes 75% less energy than the national average for college/university buildings.

Petal: Health + Happiness

Imperative: None; the team implemented its own Health + Happiness ethos

Bird-Safe Glass

Building collisions are one of the top human-related killers of birds. Up to 988 million birds die in the United States annually after flying into windows. Buildings like The Kendeda Building are responsible for a majority of these deaths. It has 9,500 square feet of windows and is surrounded by a habitat that is naturally inviting to birds.

While the Living Building Challenge does not require bird-friendly design, the project team felt that the building had to address the bird-collision problem because the Health + Happiness of wildlife should also be considered. In collaboration with the American Bird Conservancy and the Atlanta Audubon Society, the team selected a window that has visible patterns that signal to birds that they should avoid the windows.

Learn more about The Kendeda Building's bird-safe glass here: https://livingbuilding.kendedafund.org/2019/04/26/kendeda-buildings-bird-safe-glass-shockingly-huge-issue.

Petal: Beauty

Imperative 19: Beauty + Spirit

Inspired By Southern Architecture

No southern dwelling would be complete without its porch, and The Kendeda Building is no exception. Shaded by the solar canopy above, the porch of the building bridges the physical building to the surrounding landscape – eventually connecting and integrating with next phase of Georgia Tech's Eco-Commons, a greenspace complement to - and compliment of - the ideals of the building. The porch also serves as a point of entry to the building, accessible by all through several entry points.

The outdoor porch area houses several functional systems designed specifically to assist in the management of rainfall. Following the natural moderate slope from north to south, the porch terraces, or steps down, at appropriate elevations. This geometry accommodates cascading porch areas that support substantial volume storage underneath the permeable pavers. Unlike a traditional stormwater management approach that concentrates water storage in a single area, this method of managing rainwater relies upon dispersed locations along the sloped site in order to leverage gravity to assist in controlling the flow of water.

Petal: Place

Imperative 04: Human Powered Living

Pedestrian Oriented Mobility

The Kendeda Building focuses on pedestrian oriented mobility. The staircases are inviting and there is a centrally located ramp. The elevator is tucked away, out of site. This encourages physical activity by occupants.

Several campus bus routes stop at The Kendeda Building. The Georgia Tech Shuttle connects the building to public transportation. In this regard, The Kendeda Building is only one connection from Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, the busiest airport in the world!

There is zero parking provided on site. Protected bike parking is provided for full-time occupants, students, and visitors, Based on usage, biking is an extremely popular option. The porch is designed to provide shelter and cover from rain and sun while walking through the site.

Petal: Energy

Imperative 06: Net Positive Energy

Photovoltaic (PV) Canopy

To meet Living Building Challenge standards, The Kendeda Building must generate at least 105% of its annual electricity needs without on-site combustion.

The key to net positive energy is efficiency. Therefore, the design prioritized passive strategies like daylighting to reduce lighting loads, followed by efficient systems to lower energy demand—enabling a smaller solar array to meet the net positive goal.

A 330 kW solar canopy with 917 panels produces approximately 400,000 kWh annually, generating 175–225% of the building’s yearly electricity needs. This powers all systems, including lighting, HVAC, water, and plug loads. A 111 kWh lithium-ion battery provides emergency backup.

When solar output is low, the building draws from the grid. Surplus electricity benefits nearby buildings, reducing overall campus demand for utility power.

The PV canopy is also a key design feature that gets The Kendeda Building to net positive water.

Petal: Materials

Imperative 11: Embodied Carbon Footprint

Minimizing Carbon Impact

The Living Building Challenge requires projects to offset embodied carbon from construction, but the goal is to minimize this carbon pollution in the first place.

Climate discussions can be politically charged, but The Kendeda Building offers a constructive way to focus on shared goals. It uses mass timber, which is significantly lower in embodied carbon than steel or concrete, to showcase both climate benefits and economic opportunities, particularly for local wood industries.

Georgia has 22 million acres of private, commercially available timberland—more than any other state. Although some mass timber was sourced from elsewhere in the Southeast, the project underscores the potential for expanding Georgia's capacity to supply timber for commercial construction.

By using mass timber, the building reduces reliance on carbon-intensive materials like concrete. Cement, a key ingredient in concrete, accounts for ~8% of global CO₂ emissions. To reduce this impact, The Kendeda Building used low-carbon concrete technology from local provider Thomas Concrete. Learn more here.

The building also incorporates salvaged materials to further cut carbon pollution.

Petal: Water

Imperative: Net Positive Water

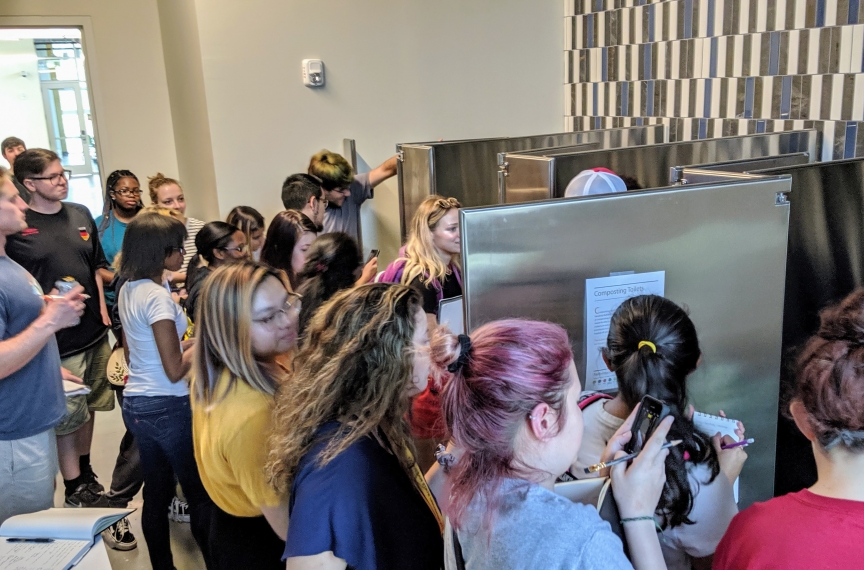

Composting Toilets

The Net Positive Water Imperative requires, among other things, that all toilet waste must be treated on-site and managed either through reuse, a closed loop system, or infiltration. For toilet waste, the design team analyzed two options: a compost toilet system and a blackwater system.

The blackwater option required more water, which would necessitate are larger cistern and a larger rainfall catchment area. This would both increase costs and conflict with square foot limitations of the building. In addition, the blackwater option had increased regulatory burdens and operational costs. Therefore, the design team selected the compost toilet scenario.

Composting toilets use about a teaspoon of water to activate a biodegradable foam to coat the sides of toilets. The waste is transported to one of six bins that are housed in the building's basement. The bins contain wood shavings that receive the waste and help natural processes decompose the waste. Because most biowaste is actually liquid, the liquids slowly seep to the bottom of the bins where a sump pump transfers the liquid, called leachate or compost tea, to one of two 1,000-gallon storage tanks. About once a month, 2,000 gallons of compost tea is transported to a local wastewater treatment facility where it is stripped of its nutrients for beneficial reuse.

These foam flush toilets have become one of the most talked about features of the building, which is why we say that there is a lot of "potty talk" in The Kendeda Building! While the excitement is all in good fun, it is also a serious matter. Atlanta has an overburdened sewer system and as a result, it has some of the highest water and sewer rates in the country. Because the building's compost toilet system does not connect to the sewer, it does not burden an already stressed system. Moreover, the composting toilet system eliminates the carbon pollution embedded into the electricity required to treat and convey water and wastewater.

Petals: Equity and Water

Imperative: explicit – Net Positive Water; however rainfall management is an Equity consideration

Reducing Burden To Downstream Communities

Rainfall is often overlooked as an equity issue. In most urban environments, it’s treated as stormwater—something to quickly divert using infrastructure, rather than manage as a resource. Most buildings send rainwater into sewers or streets, and impervious surfaces like asphalt and concrete prevent water from being absorbed into the soil. This “not in my backyard” approach shifts the problem downstream, where flooding and other consequences often affect underserved communities.

Even moderate rain events can cause localized flooding and strain infrastructure. For an example of this impact near Georgia Tech, visit the West Atlanta Watershed Alliance.

Recognizing that The Kendeda Building sits upstream in the Peachtree Creek watershed, the design team approached stormwater with an equity lens. Their decisions were guided by Living Building Challenge standards, which led to a landscape that mimics the native Piedmont Forest—an ecosystem capable of retaining 90% of rainfall from typical storms. The site now performs more like a forest than a building.

Rainwater is captured from the solar canopy, green roof, and roof deck, filtered, and stored in a 50,000-gallon cistern in the basement. This system captures roughly 41% of annual rooftop runoff. Once the cistern is full, excess water flows into bioswales and pervious surfaces around the site, where it gradually recharges the groundwater. Moreover, the building is surrounded with pervious surfaces and bioswales that allow for water to slowly seep into the ground.

If more buildings followed this model, stormwater could shift from being a burden on infrastructure to an asset.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

An Evolving Standard

Each new Living Building advances regenerative buildings, contributing real-world data and feedback to refine LBC standards. The Kendeda Building met the requirements of LBC 3.1, but as Living Future continuously updates the certification, future projects should refer to Living Future’s website for the latest guidelines.